Built in 53 Days. Here for 125 Years.

By Bob Yates

July 2023

Note: This is an updated version of a similar piece which appeared in the July 2018 issue of the Boulder Bulletin, on the occasion of Chautauqua’s 120th anniversary.

Imagine a mid-spring day in 1898, a mile south of the small town of Boulder, Colorado. It is May 12 and a group of high-minded school teachers has just arrived from Austin, Texas, prepared to build a “chautauqua” on the site of a cattle ranch at the base of the iconic Flatirons. Only a month earlier, the 5,000 residents of Boulder had passed a bond issue, formed a “Committee on Parks,” and purchased a 75-acre ranch from the Bachelder family. On that mid-May day, the teachers from Texas, joined by Boulder community leaders, set out on the ambitious task of creating a new city—complete with dining hall and auditorium—in 53 days, so that it could be inaugurated on July 4.

And they did it. At 10:30 on the morning of July 4, 1898, with the paint on the dining hall walls still drying, more than 4,000 people from Colorado and Texas gathered in the new auditorium, and on blankets on the lawn around it, accompanying a concert band in the singing of “America” and “Dixie.” This week, during the 2023 Fourth of July week, their descendants from Colorado and Texas will gather at Chautauqua, a tradition unbroken for 125 years.

The Chautauqua Movement began in Upstate New York in 1874 on the shores of Lake Chautauqua, started by a Methodist minister and a businessman hoping to train Sunday school teachers during the summertime. Soon, hundreds of replica “chautauquas” sprung up across the country, often tent cities on the edges of towns, where families could escape the summer heat, get a little religion, and hear some secular speakers as well. Some families stayed only a few days, some the entire summer, if their economic conditions permitted.

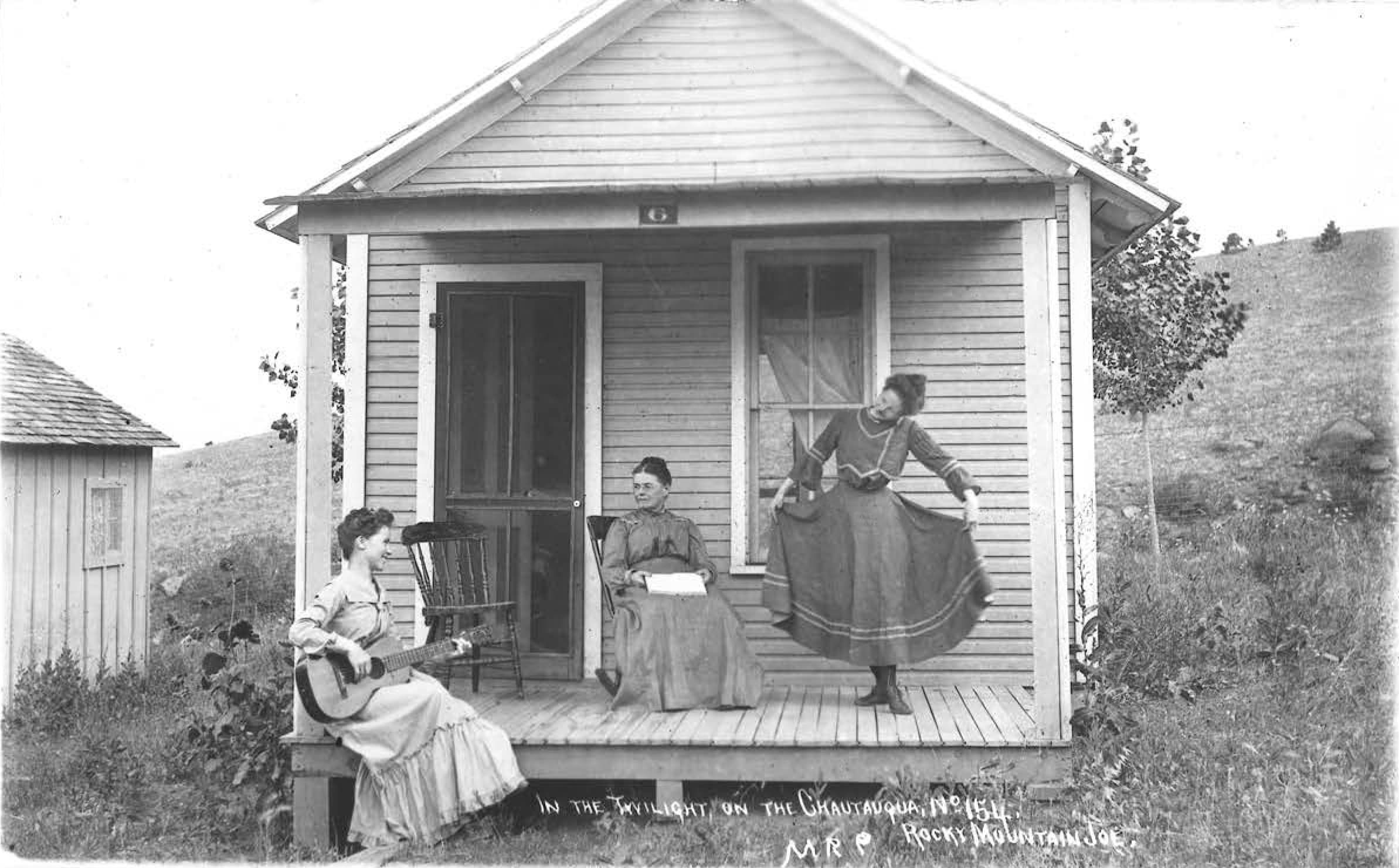

A nationwide Chautauqua speaker circuit sprung up, bringing the likes of evangelist Billy Sunday and political orator William Jennings Bryan to small towns across America. Edison’s newfangled moving pictures were projected on white tent walls, silent but accompanied by piano or organ. Homemaking instruction was offered for women and science classes for children. Musical recitals and plays were performed in the evenings.

At a time when attending college—or even high school—was a luxury, a Chautauqua could provide some higher education and an introduction to a little culture. By the end of the 19th century, the whole endeavor had become more sophisticated, with groups from the South seeking out cooler northern climates for the summer, and permanent buildings replacing tents. The 1898 formation of the Texas-Colorado Chautauqua in Boulder epitomized these changes, with permanent cottages at the foot of the Flatirons joining the dining hall and auditorium in 1899.

By the 1930s, the Chautauqua Movement began to wane in the United States, suffering from competition with radio and talking movies. The ubiquity of automobiles provided rural families opportunities to travel farther, to cultural amenities in big cities. By World War II,

nearly all of the thousands of chautauquas across the country had disappeared. But, thanks to the persistence of both annual summer visitors from Texas and year-round Boulder residents, the Colorado Chautauqua in Boulder survived. Today, it is one of only three of the original chautauquas in the country, and the only one to operate year-round.

Colorado Chautauqua’s CEO, Shelly Benford, feels that, in many ways, the place has stayed true to its roots. “Although there are many more options for learning and entertainment now,” Shelly explains, “Chautauqua remains a special place for those who crave community, while enjoying the benefits of lifelong learning and the finest entertainment.”

The Colorado Chautauqua campus is now 26 acres owned by the City of Boulder and leased long-term to the non-profit Colorado Chautauqua Association (yours truly negotiated the latest 20-year lease extension when I served on the association’s board a few years ago). In addition to the original 1898 dining hall and auditorium, the campus is served by a 1900 Academic Building (now the association’s offices) and a 1918 Community House, where more intimate concerts and programs are offered.

There are 99 cottages (don’t call them “cabins”), mostly built in the early 20th century, and ranging in size from a few hundred square feet to four bedrooms. Two-thirds of the cottages are now owned by the association, which leases them during the summer to families staying just a day or two, or for several weeks. During the off-season, the cottages are often rented to longer-term occupants, like visiting CU professors or local Boulder families needing housing during extensive home remodels.

The other one-third of the cottages remain in the hands of owners, who refer to themselves as “cottagers.” Some, like my friends Maude and John Kenyon, came to Boulder a few years ago to enjoy the Chautauqua lifestyle year-round. But a few of today’s cottagers are fifth, sixth, and seventh-generation descendants of the original 1898 Texas school teachers, making the annual pilgrimage to Boulder for a few weeks in our cool summer climate. Walk around the cottages in the summertime and you can find them through their Texas license plates.

The grounds around Chautauqua today are undoubtedly more pleasant than the tent-strewn converted cattle ranch that first summer in 1898. Mature trees, some now 125 years old, provide shade above lush green lawns, intersected by meandering paths. Shelly explains that, over the past five years, the association has invested $18 million to make the grounds pleasing for both day visitors and overnight guests. A few years ago, the dining hall was completely updated and local chef Lenny Martinelli (of Dushanbe Teahouse fame) was brought in to provide the restaurant service.

But some things haven’t changed much in 125 years. The auditorium still plays silent films and hosts political orators (Al Gore was there a few years). The Colorado Music Festival calls Chautauqua home and often performs classical pieces that would be familiar to an 1898 audience. And while tastes in contemporary music have shifted over 125 years from John Philip Sousa to the Indigo Girls, folks can still sit on blankets on the lawn outside the auditorium and enjoy a free concert.

One other thing that hasn’t changed in 125 years: Transportation. It’s always been a challenge getting folks up and down that hill. After Chautauqua’s first successful summer in 1898, local leaders built an electric rail trolley between downtown Boulder and Chautauqua in time for the 1899 summer season. The fare was five cents, the trolley ran every 15 minutes between 7 a.m. and 11 p.m., and passengers were encouraged to bring their bicycles aboard. The trolley ceased operation in the 1930s, during Chautauqua’s lean years.

In recent decades, hundreds of thousands of annual visitors flock to Chautauqua and the adjoining Open Space, creating traffic and parking headaches for all. However, it took us a long time to figure out how to replicate the 1899 trolley. In 2017, after years of hand-wringing over the transportation challenge, the city initiated a “Park-to-Park” free bus shuttle between parking locations around town and Chautauqua. Shelly declares the shuttle a success, pointing to the decreased traffic and parking problems at the park. “It is an example of a truly collaborative project between the city and Chautauqua,” Shelly says. One wonders why it took us decades to find a solution to a problem that, in 1899, they fixed in a few months.

Shelly has led the Colorado Chautauqua for seven years. As she looks ahead, she believes that one of Chautauqua’s biggest opportunities is expanded access. “I feel that there is more we can do to make Chautauqua feel more welcoming and accessible to a larger segment of the Boulder community,” Shelly says. “We have lots of events up here, and they are well-attended. But, there are many in the community who still cannot take advantage of what we offer.”

A former member of the BVSD school board, with a professional background in finance and strategic planning, Shelly is well-positioned to find the less-advantaged in our community—particularly children—and bring them to Chautauqua for meaningful cultural experiences. A few years ago, Shelly launched Chautauqua’s first-ever summer camp for local kids, including scholarships to ensure that no one is turned away due to lack of resources. And today Chautauqua hosts a free, bilingual Festival de Sol, which celebrates Latino culture.

Shelly shares her favorite places in the peaceful setting: “The porches at Chautauqua are the best places to relax and hang out with friends,” she declares. But, this week, Shelly will be hosting 125th-anniversary parties. The big community bash will be on Saturday, July 8, with history exhibits, tours, food trucks, and live music on the green. Who knows, maybe someone will play Dixie.